(LINKS

TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth

Science Instructor: Arthur Reed, P.G.

Happy

Fossil Friday!

Friday October 16, 2020

Instructor: Arthur Reed, P.G.

Seafloor

Fossils on the Summit of Mt. Everest?

Earth

is Dynamic!

The

summit of Mount Everest, the highest point on Earth, is an ancient sea

floor. It is limestone with fossils of trilobites, crinoids, brachiopods,

ostracods, and others...all life from an ancient ocean floor. The rocks

at the top of Mt. Everest (where climbers spend a fortune to stand) formed from

sediment on the floor of the ancient Tethys Sea (or possibly a pre-Tethys Sea)

in the range of 450 million years ago. Its floor was pushed up into the

Himalaya Mountains by India colliding with Asia in the process of plate

tectonics starting around 55 million years ago.

See Full Article Below

Fossils of Mount Everest

The summit of Mount Everest, the

highest point on Earth, is a sea floor. That may come as a surprise; after all,

a sea should be at sea level. In practice, there is some flexibility on this.

Three seas are below sea level: the Dead Sea, the

Salton Sea and the Caspian Sea. All are salt water lakes

which carry the name sea. There is a fourth one, the Aral Sea, which is above

sea level. Its water surface (at least what remains of it, after one of the

biggest environmental disasters of the 20th century) is

currently 42 meters above sea level, and it can therefore claim to be the highest

salt-water sea on Earth. It is still some way off Everest though. There is one fresh water lake which is called a ‘sea’: the Sea of

Galilee, but it is also below sea level. Lake Baikal is called ‘sea’ by the locals, but not

in its official name – if it did, it would have been the highest sea on Earth, at

455 meters. The highest fresh-water lake on Earth is reported to be the crater

lake of the Argentinian volcano Ojos del Salados which

is at 6930 meters. However, it is rather small, at 35 meters, and by definition should be called a pond rather than a lake. Cerro

Tipas Lake at 5950 meters is the next best candidate.

There are some higher bodies of water in the Himalayas

but they are ephemeral. But every single one of them is topped by the summit of

Everest. It is perhaps a bit sobering to think that people who sacrifice their fortune

and potentially their lives in order to climb Mount

Everest, end up standing on a sea floor.

A sea floor should be lower than the sea it

floors. Clearly, things have happened here that turned a sea floor into the

roof of the world. The story behind this involves the highest fossil hunting on

the planet, and not one but two lost oceans. It shows how trilobites managed to

beat Nepal’s famous Sherpas, by hitching a ride with a carrier, becoming cargo

to the mountain itself.

The presence of marine fossils near the summit

of Mount Everest has entered the domain of common knowledge. Many posts,

articles, and newspapers state that sea shells are

found at the summit. But few give the source of their information – it is just

something that ‘everyone knows’. And there is confusion about the fossils of

Mount Everest. Shells are commonly mentioned, of varying sizes. A few sites

mention ammonites, and I even found one that claimed the presence of fish. Try

to find the source of their information and you quickly hit blanks and dead

links. Who did the fossil collecting? Most people climbing Mount Everest do not

go there to hunt for fossils. Their goal is to reach the summit – not to bring

down the mountain. On the way up, you don’t want to

carry rocks with you. On the way down, your main aim is staying alive, while

frozen and oxygen-deprived. Where are the fossils of

Mount Everest? And what are those fossils?

Facts

First, let’s

clear up some confusion. How did a mountain shared between Tibet and Nepal end

up with an English name? You can blame the Royal Geographical Society for that.

This was the age of the exploration, and what is the point of exploring if you can’t give names? Marquez’ master piece, One hundred years of solitude, describes when the world was so recent that many

things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. This was not

the British way. Names were needed. Mount Everest had not been noticed at first

as being particularly impressive. The exploring had to be done from a

considerable distance, from Tibet, as the explorers were not allowed entry into

Nepal. Foreshortening meant that other peaks appeared taller. In the 1840’s,

the first indications appeared that a distant peak could be taller than any

other. For a while it was called ‘peak b’, and later it became ‘peak XV’, but

that wouldn’t do. When no local name could be

identified, it was finally named after George Everest, Surveyor General of

India. The pronunciation evolved, with the long ‘e’ becoming a short one, but

otherwise the name stuck. The new pronunciation had a ring to it: it sounded

like a special place.

However, unbeknown to the explorers, a Tibetan

name was already in existence. It was Qomolangma, and

that name is now often used. Nepal has since adopted yet a different name,

Sagar-Matha. Pick your choice: whichever name you

use, at least you no longer have to point.

And what about the height? Nepal and China,

who share the summit, quote different numbers for it. Nepal uses the

traditional 8848 meters. China claims it is only 8844 meters. The first number

refers to the actual altitude climbers reach when standing (very briefly –

there is a queue) at the summit. They are standing on 3-4 meters of snow. The

second number gives the rock height which is a more stable way to measure a

mountain – but it isn’t as high so it didn’t catch on.

People who climbed the mountain from the Tibetan side would find their

achievement listed as 4 meters less than those climbing the same mountain from

Nepal. When spending a fortune, such details matter.

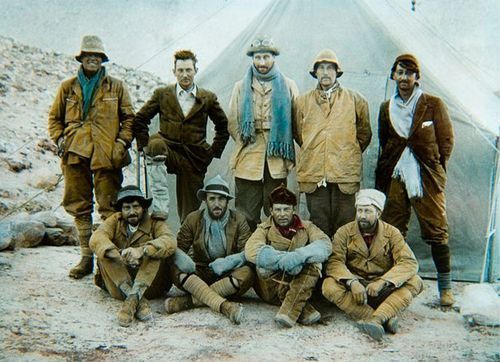

The 1924 Everest expedition. Back row, left to right: Andrew Irvine,

George Mallory, Edward Norton, Noel Odell, and John Macdonald. Front row:

Edward Shebbeare, Geoffrey Bruce, Howard Somervell,

and Bentley Beetham.

But regardless of the name and

the height, Mount Everest is a very dangerous mountain.

The sheer number of people climbing it in the brief annual climbing season does

not help. But the statistics of the mountain are sobering. For the Sherpas, the

fatality rate is between 1% and 4% per year. Avalanches

during the pre-season preparations are especially deadly. Almost 300 people

have died on Mount Everest since 1950. Among them is the NASA astronaut and

astronomer Karl Henize – but many other names could

be mentioned. George Mallory, who disappeared near the summit together with

Irvine in 1924, was born very near to where I now

live. The chase of Everest connects the world.

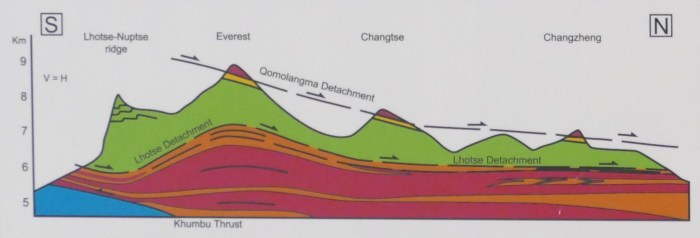

The layers of Everest

The triangular mountain is

instantly recognizable. If you haven’t studied the shape in detail, try

this gigapixel view. But it is easy to miss the detail in the

mountain. There are several layers. For instance, there is a region with inclined

layered bedding, a bit below the summit, clearly visible at the bottom of the

summit pyramid.

The second most famous pyramid in the world

The structure of the mountain is a bit hidden

behind the snow. Sweep the snow away, and four main layers appear. The same

layers are also visible in the other mountains in the area.

Source: http://www.earthsciences.hku.hk/shmuseum/earth_evo_08_2.5.2.5.php RF:

Rungbok formation; ES: Everest Series; YB: Yellow Band;

OF: Qomolonga Formation (Everest limestones)

The layers are colour-coded

in the drawing shown here. The bottom layer is colour-coded

in brown, and labelled ‘LG+RF’. ‘RF’ stands for Rungbok Formation and ‘LG’ is a granite. RF is a gneiss:

rock partly melted and metamorphosed under high temperatures (up to 500 C) and

pressure, deep below the mountain. The granite was molten crustal rock from

below which pushed its way up into this layer, much like granite complexes have

done at the heart of every mountain chain. A low-angle (almost horizontal)

fault separates the layer from the one above, which is colour-coded

in green. This layer is called the Everest Series (ES), and it consists of

sedimentary rock which has been metamorphosed at reasonably high temperatures.

Above this, in yellow, is the so-called ‘Yellow Band’. This is the layered

bedding which was mentioned before. It is a limestone, formed from a shallow

marine sediment, heated to become a marble. Above this is another

near-horizontal fault, and above this is an almost unmetamorphosed layer of

limestone here called ‘QF’ for Qomolangma Formation,

which forms the summit of Everest. The layers have moved around: the two faults

are planes along which the layers have been sliding into their current

position. The upper layers didn’t form exactly here,

nor did they form in the same place. They are short-distance migrants.

Look at nearby mountains, and the same layers

may be seen in the same order, although not at the same altitude. From south to

north, the layers decline in altitude. The mountain building that pushed them

up in the first place, caused by crustal thickening and intrusion of the

granite, was strongest around Mount Everest but less severe further north. The

fact that the layers don’t invert shows that in this

location, the sliding was a simple process. There was no turn-over of layers as

happened elsewhere, and as is seen in the Alps or Caledonian mountains. Around

Everest, the upper sediment that has been least metamorphosed is always at the

top. But few mountains are high enough to reach them: in most cases, erosion

has removed this layer completely. There are nine mountains over 8 kilometer

high in the high Himalayas. Of those, 6 still have a sedimentary layer at the

top.

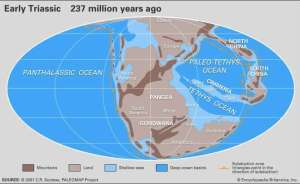

The Tethys Ocean

The top layers of Mount Everest are made from

a marine sediment: a sea floor. But which sea? Or rather, which ocean? To

answer this, we need to go back to the heady days when the Himalayas formed.

The Himalayas were a long-delayed

consequence of the break-up of Gondwana. Australia, Africa, South America, India and Antarctica were all together in this

supercontinent. (The world rugby competition between Gondwana and its

northern-hemisphere counterpart, Laurussia, must have been a very one-sided

affair!) Gondwana began to break up along the east coast of Africa where a fault grew into the Indian

Ocean. In the process, a fragment was split off and became adrift in this new

ocean. The fragment split further, into Madagascar and India. Madagascar stayed

behind, but the fault behind India rapidly widened into an ocean and India was

pushed forward, north. Between India and Asia was the Tethys: a worldwide,

equatorial ocean running from China to Central America.

So India went across,

closing the Tethys in the process and forming the Indian Ocean behind it. The

seafloor that was uplifted and shifted to Everest was from the Tethys. It wasn’t the deep ocean basin: that was mostly subducted. The

mountains grew from the continental shelf, and pushed

up the sediment that was lying on it. The Tethys just disappeared. A few scars

remain which trace the lost ocean. Some have already been mentioned: the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea and even the Aral Sea trace

out the line where the ocean once was.

This is the basic view, In

reality, things were a bit more complicated. I’ll come

back to that.

Collision

50 million years ago India completed the

crossing, failed to stop, and crashed into Asia. The collision happened in two

phases. First, India hit an island chain. This was a volcanic island arc that

had grown out of the subduction zone. The island arc left its sign in northern

Pakistan. Later, India hit Asia, beginning in the northwest

and ending in the northeast, in a drawn-out process. Originally, India had

moved at break-neck speed, covering the distance at up to 20 cm per year. By

the time of the initial collision, India had slowed down to 5 cm per year. This

was still well above the speed limit for safe continental docking, though. The

continental plate of India slid underneath Asia, and crumpled.

The Himalayas are the crumple zone of that collision. The granite that forms

the heart of the Himalayas consists of the Indian plate, melted at the high

pressures at the bottom of a crust thickened to 70 kilometers.

The collision left India a lot smaller than it

used to be. At 5 cm per year, India has lost 1000 kilometers over 20 million

years. And still it is moving. It is hard to stop a continent.

So the Himalayas grew

from below. In the process they pushed up the layer of seafloor sediment. Once

the new mountains pulled in the rains, erosion attacked them. It removed the

material from the top. In consequence, very little of the old seafloor that

formed the upper reaches remains: only those 6 of the

highest peaks just reach the Tibetan marine deposits. The rest of the old sea

floor has been carried away by the giant rivers of the Himalayas,

and returned to the Indian Ocean.

Fossils

The ancient sea floor will have

incorporated the organic remains of ocean life. Fossils are relatively fragile:

they can survive a modest amount of heating of the rock, although it may push

then out of shape. But there are limits. You expect fossils in sedimentary

rocks and in mildly processed metamorphic rock. By the time the rock

becomes greenschist, any fossils will be gone.

A schist from high up on Mount Everest. Source: https://palaeomanchester.wordpress.com/2017/12/14/reaching-new-heights-with-collecting-everest-specimen/ It

was collected at around 8 km altitude and that is impressive enough. But it is a

schist and as such contains no fossils.

The lower layers of Everest are indeed greenschist, and are not great for fossils. The granite was

injected from below and has been through worse: no fossils here. The Yellow

Band is a marble, heated enough that only microscopic fossils may be left. The

upper-most layer is limestone and although it has seen elevated temperatures

and pressures, it remains suitable for fossils – if you don’t

expect too much! It is found above 8600 meters.

The most interesting fossil rock of Everest

will therefore be those nearest the summit. But they are also the hardest to

get hold off. You can’t just jump on a plane to go

collect an Everest summit rock! Luckily, we don’t entirely

depend on the mountain itself: because the layers tilt downward towards the

north, the same (or similar) rocks can be collected at slightly more reasonable

altitudes. The Rongbuk Glacier in Tibet is such a

place, and a lower layer is named after this location. But in the end, the

fossil scientists wanted rocks from the mountain itself.

The first rocks from the upper layers were

collected already in 1922, at an altitude of 8200 meters. More were collected

in 1924, on the very day (and the same expedition) that Mallory and Irvine

disappeared into the clouds. There were more samples collected over the next

years, but many were stolen in 1939 and the notes describing them destroyed two

years later. Expeditions of various nationalities brought back new rocks over

the next decades.

The limestone is light in colour. It consists

of layers of bedding, as narrow as a few millimetres,

with alternating sand and calcareous (chalk) bands. The bands have colours varying from white to dark grey. The sand seems to have

come from eroded granite: it was an erosion product from the land, brought down

by rivers and collected in sand banks. It comes from mountains that came before

the Himalayas, but how much earlier is impossible to tell.

Both the sand and the chalk contain fossils, tiny but clear. ‘Tiny’

here means that you need a microscope to see them: the sizes are something like

a millimetre. It is quite a contrast with the size of

the mountain!

Here are two examples, from the work

of Professor Ganser, Geology

of the Himalayas (1964) and reproduced by Noel Odell in 1974,

in the Geological Magazine. (Click on each image to see the full resolution.)

Odell was one of the original members of the 1924 Everest expedition. Both

examples show fragments of crinoids. Crinoids are better known as sea lilies;

their relatives include starfish and sea urchins. Sea lilies have been around

since the Cambrian. Nowadays, they are found in deeper water, below 200 meters,

but in the deep past they lived in shallow waters, and

formed complete forests. Limestone beds can be made up entirely of such

creatures: they were that abundant.

A sea lily, from the Gulf of Mexico. Organisms related to this one

were abundant in the sediments that became the summit

of Mount Everest. Photo: NOAA

Material from the Yellow Band has

shown that it too contains up to 5% crinoid fragments. Other fossil fragments were

found in the limestone: trilobites, brachiopods (lamp shells), and ostracods

(small shrimps). Below about 70 meters below the summit there is a layer that

formed from trapped sediment, 60 meters thick. The sediment was caught in a

biofilm, probably from cyanobacteria (algae). This kind of bacterial mat is

called a thrombolite, and forms in very shallow marine water. The thrombolite

bed forms the bottom of the summit pyramid, including the ‘third step’.

The highest rocks that have been brought

down were collected from 6 meters below the summit! They were collected in 1997

by a Japanese climber, M. Sawada; the analysis was published by Harutaka Sakai and collaborators. Two images from their

work with fossil fragments are shown here.

The left image shows a polished slab of the summit limestone. The

bar at the bottom is 1 centimeter. It shows bedding and faulting; fractures are

filled with calcite. On the right is an enlarged polished surface showing crinoid

and brachiopod fragments; the bar is 1 mm.

Left: grainstone with skeletal grains of

trilobite (T), crinoid (C), ostracod (O) and fecal pellets (P). The bar is 1mm.

Right: T trilobite fragments with the typical threefold arched shape. The bar

is 0.1mm.

The Tethys and

what really happened

How old are those fossil fragments? You might expect it to have the

age of the formation of the Himalayas: some 40 million years. But no. The fossils

are Ordovician to middle Cambrian, around 520 to 450 million years old. These

dates have been confirmed by analysis of zircon grains of the Yellow Band. The

sea floor, or rather the continental shelf, that became the summit of Everest

was ancient! It was much older than the mountains themselves. The sediment had

been on the sea floor for a very long time, before

India came and scooped it up.

There is something funny here. The Tethys Ocean first formed around

275 million years ago. That makes the ocean considerably younger than the age

of the fossils. Mount Everest couldn’t have come from

the Tethys! The fossils lived when the ocean wasn’t there

yet. The typical life time of an ocean is 200 million

years: by that time, the oceanic crust has cooled so far that it becomes denser

than the mantle below, and it begins to sink. A subduction zone forms which

swallows the ageing ocean. The difference in age between the fossils and the

Tethys correspond to this age. Mount Everest grew out of the previous

generation of ocean.

Indeed, before the Tethys formed,

there had been another ocean. Nowadays it is called the Paleo-Tethys. In those days,

of course, the world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. Originally, Gondwana

and Laurussia were separated by this Paleo-Tethys.

Around 290 million years ago, a fault developed in Gondwana. It became

a spreading ridge and experienced intensive flood basalt eruptions. The area to

the north of the spreading centre split off from

Gondwana. It was a fairly thin, long fragment, consisting

of Turkey, Iran, and Tibet. Behind them, the spreading ridge quickly became an

ocean: this is what became the Tethys (sometimes called the Neo-Tethys). The

flood basalt was carried with: the remnants can be

found as the Panjal Traps in Kashmir. The cause of

this early split of Gondwana is disputed. There is no strong evidence for a

mantle plume. It may have been an older, passive fault which became activated

when the old Paleo-Tethys began to subduct, and started

to pull on Gondwana.

The fragment that included Tibet moved towards Asia, in the process

closing the Paleo-Tethys ocean in front and opening the Tethys ocean behind it.

200 million years later, the process replayed itself. Again

a subduction zone had formed as the Tethys was reaching the end of its life. Again Gondwana spit, this time terminally. India declared

independence and started its journey towards Asia, chasing after Tibet.

The collision now occurred in stages. First, the remnants of the

Tethys were swept up as the fragment of Tibet was driven into Asia. This formed

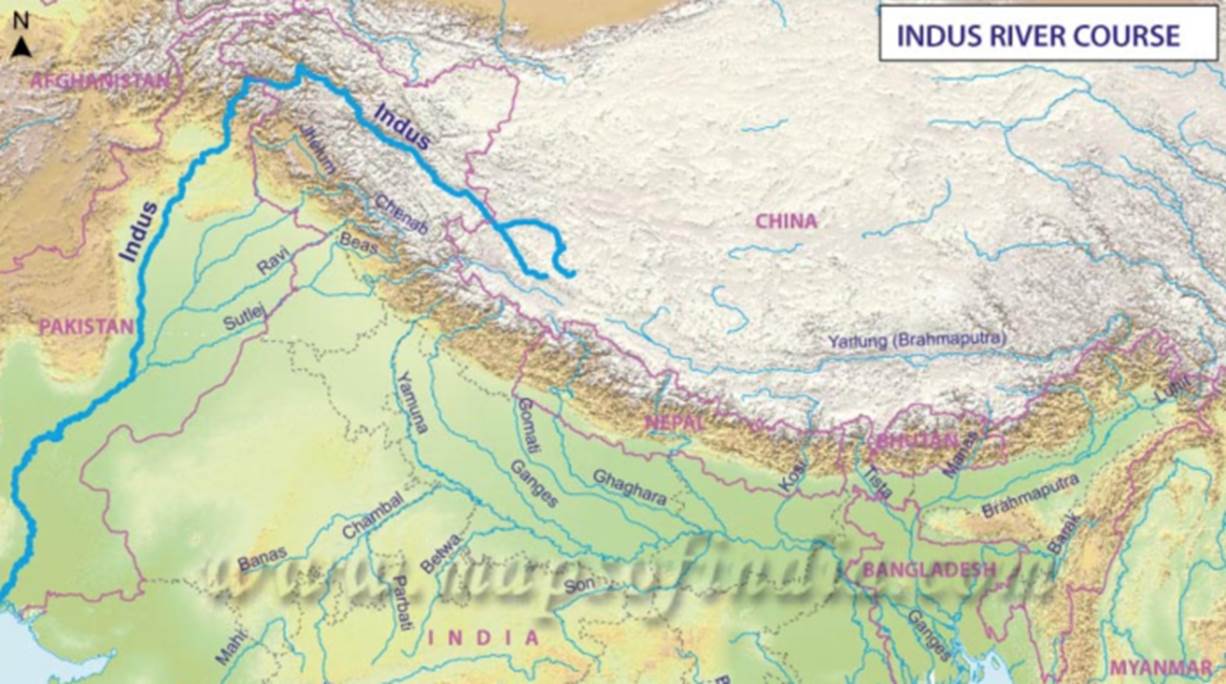

the first mountain range, the Trans-Himalayas, around 55 million years. The range

is still there: it lies north of the high Himalayas, starting from Kasmir. It runs parallel to it for over 1500 kilometers, with

peaks over 7 kilometers high. The range lacks the clear structure of the river valleys

of the high Himalayas. This is because it formed first, before the rivers were

there. The rivers began to flow from the range, including the Indus.

Immediately to the south, the Tethys-Himalayas were also uplifted. This included

the old sea floor. The process here was gentle, with little metamorphism.

Next, India arrived. This collision threw up the High Himalayas,

south of the Tethyan range. The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers were already there,

flowing from the Trans-Himalayas and through the Tethys-Himalayas. Both cut

through the newly rising mountains: you can see that they originate behind the

high mountains, showing that they predate it. The rising was a prolonged process.

The current high Himalayas were build

on granite emplaced around 20 million years ago. The rising of the high Himalayas

continued in phases, and is still on-going. India isn’t finished yet.

Source: wikipedia

The progressions of oceans is still seen

in the Himalayas. The shore of old Laurussia became the Trans Himalayans. The

continental shelf of the Paleo-Tethys was uplifted to form the Tethys-Himalayas.

The new shore line facing the Tethys ocean became the

High Himalayas, underplated by the Indian subcontinent.

So how did the Paleo-Tethys sediments end up on Everest? You may

blame the near-horizontal fault that runs between the limestone of the Qomolonga Formation and the Yellow Band. It provided a low-friction

contact. As the Trans Himalays rose

up, the limestone layer slid down, towards the south. When the High

Himalayas formed, the old Paleo-Tethys floor was ready and waiting. The

mountains formed underneath it, sediment from an ocean that had vanished in the

earlier collision.

Raising the roof

When you climb Mount Everest, you are not just reaching the summit

of Earth. It is also a journey back in time. The mountain is young, as mountains

go: the granite at its heart is no more than 24 million years old. One day,

erosion will have taken it down to the level of this granite. But not yet. For

now, remnants remain of the older surface that was here before the mountain

grew up. The fossils, microscopic and broken down they may be, show that this

surface is old as the mountains, by manner of speaking. They date back to the

Cambrian. The Indian Ocean is the grand child of the ocean in which they lived.

The fossils survived not one but two continental collisions.

The summit of Mount Everest is so much older than the mountain itself.

It was deposited when even Gondwana was young. Climbing Mount Everest takes you

to a time when life was young and many things lacked

names. Even if the fossils are only a millimetre across

– it is worth bringing some down, back to the sea where once they came from.

Albert Zijlstra, June 2018