(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth

Science Instructor: Arthur

Reed, P.G.

Happy

Fossil Friday!

Friday March 19, 2021

Our

destiny was set before the rise of the dinosaurs

Before

the great extinction at the end of the Permian, a group of tetrapods (four

limbs with a vertebrae) had moved away from other tetrapods as the bases of the

subclass Synapsida. These included

interesting animals like the Dimetrodon shown below. Some in this class evolved into borrowing

mammals in the Mesozoic (while hiding from the dinosaurs!) and

eventually led to all modern-day mammals including humans. Below is a short article from The Fossil

Non-Mammalian Synapsid Collection at ‘The Field Museum of Natural History’ in

Chicago, and a link to an informative PBS video.

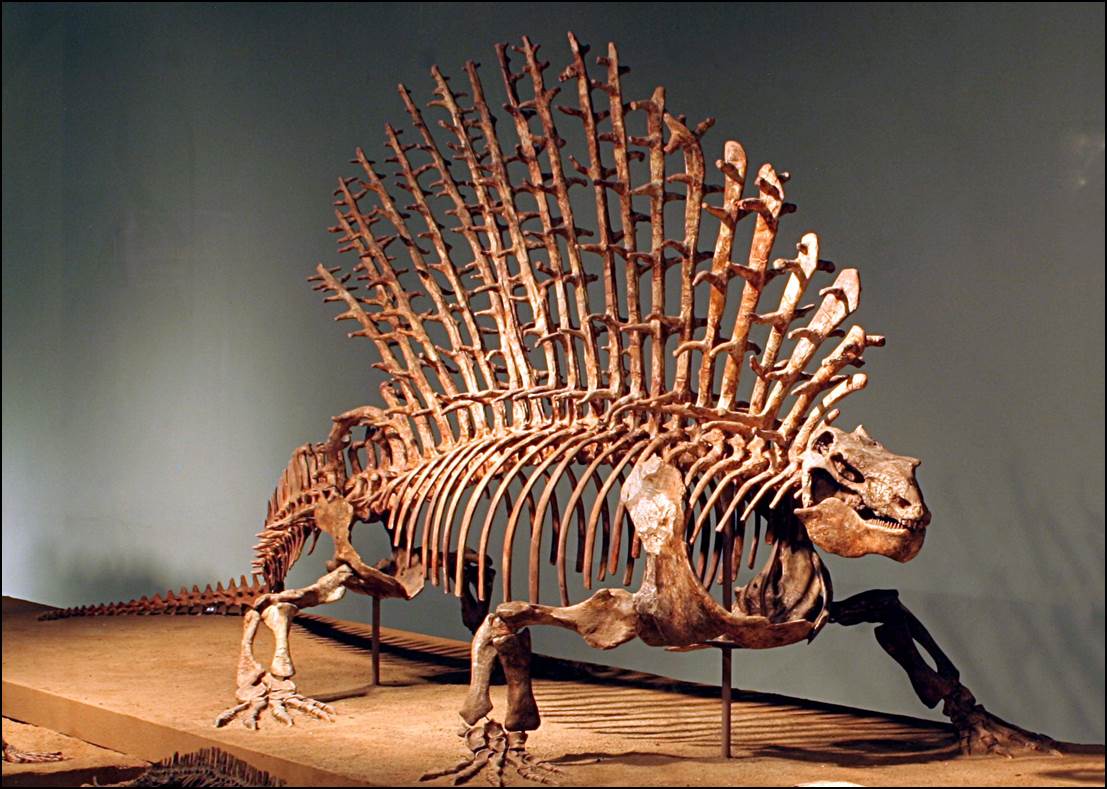

Photograph

of a skeleton of the early non-mammalian synapsid (ancient mammal relative)

Edaphosaurus on display at the Field Museum of Natural History. Credit:

Photograph by Ken Angielczyk

Video:

‘The Synapsids Strike Back’

Introduction

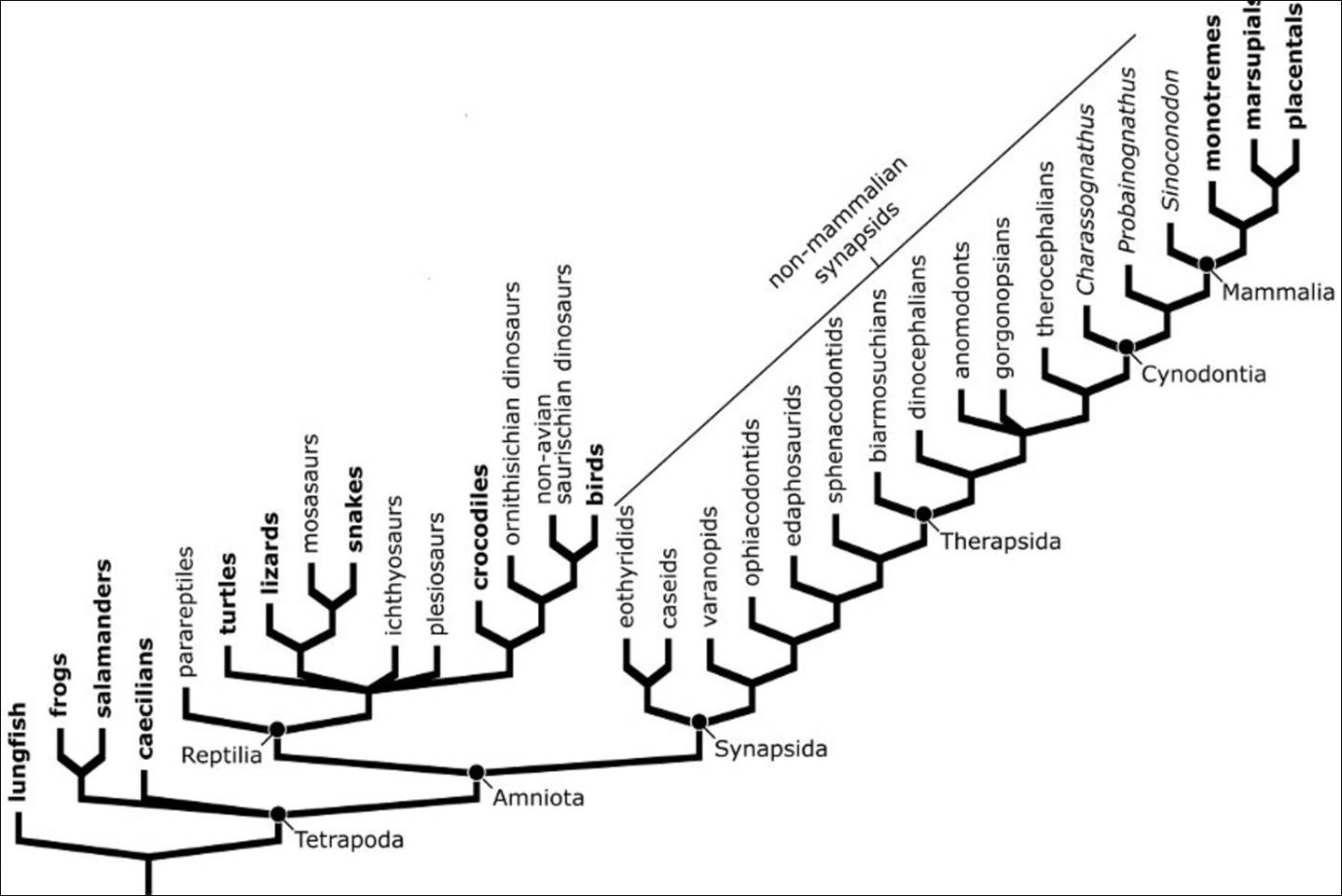

Amniote

tetrapods (i.e., those terrestrial vertebrates that produce eggs in which the

embryo is surrounded by a series of extra-embryonic membranes) in the modern

world can be divided into two great lines of descent, the Reptilia and the

Synapsida. Extant reptiles include lizards, snakes, turtles, the worm-like

amphisbaenians, crocodiles, and birds, while monotreme, marsupial, and

placental mammals are the extant representatives of Synapsida. The reptile and

synapsid lineages both descend from a common ancestor, but that divergence is

ancient, occurring in the Carboniferous Period of Earth history (approximately

315 Mya). The first true mammals appear in the fossil record about 200 Mya,

near the end of the Triassic Period. If we consider a phylogenetic tree that

shows patterns of descent from common ancestors, we can see that there is a

large number of extinct members of the synapsid lineage that existed between

the origin of Synapsida and the appearance of mammals.

Simplified

phylogeny showing relationships among tetrapods. Groups with living members are

shown in bold; extinct groups are in plain type. Modified from Angielczyk

(2009).

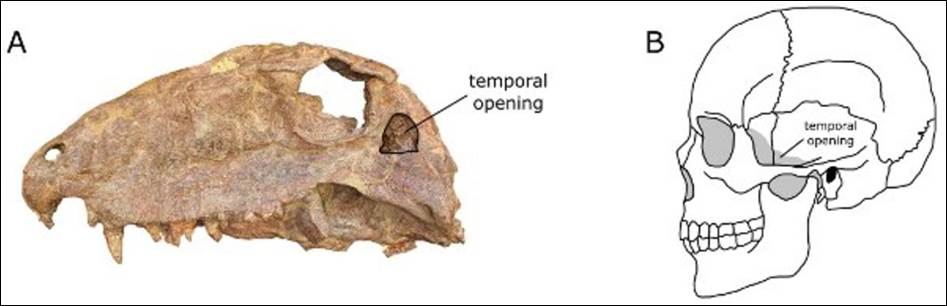

A

single temporal opening around which jaw muscles attach is a feature shared by

all synapsids. A. location of the temporal opening in the

Early Permian synapsid Dimetrodon (FMNH UC 40). B. location

of the temporal opening in a human skull. From Angielczyk (2009).

These

extinct synapsids are often referred to as “mammal-like reptiles” because some

have a superficially reptilian appearance. However, all are descendants of a

common ancestor that existed after the divergence between Synapsida and

Reptilia, which means they are all more closely related to extant mammals than

to any reptile. A more accurate name for these extinct species is

“non-mammalian synapsids,” which reflects the fact that they are members of the

synapsid lineage, but are not mammals.

Non-mammalian

synapsids are an extremely important part of the fossil record because they

document the evolutionary history of many of the distinctive features of

mammals, such as the presence of a bony secondary palate, the incorporation of

bones from the lower jaw into the middle ear, teeth with complex occlusion

patterns, and upright limbs. Morphological features, such as the presence of a

single opening behind the eye socket around which jaw musculature attaches,

help us recognize members of the synapsid lineage in the fossil record. An

introduction to non-mammalian synapsids can be found in Angielczyk (2009).