(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL

FRIDAYS)

(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL

FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth

Science Instructor: Arthur Reed, P.G.

Happy

Fossil Friday!

Friday April 2, 2021

How

is it possible for a footprint to be preserved 100 million years or longer?

If

it is made under the right conditions (damp soft ground), followed by the right

type of burial (rapid before the print is disturbed), followed by the right

lithification process (lithified into durable sedimentary rock), followed by

the right erosional sequence of overlying materials (overlying material eroded

away without eroding the footprint), and then followed by someone finding it

during the short time it is exposed at Earth’s surface (before it is

permanently erased by continued erosion)…only then will it be available for us

to study and enjoy. Only a tiny fraction

of ancient footprints make it through these (and other unforeseen) steps.

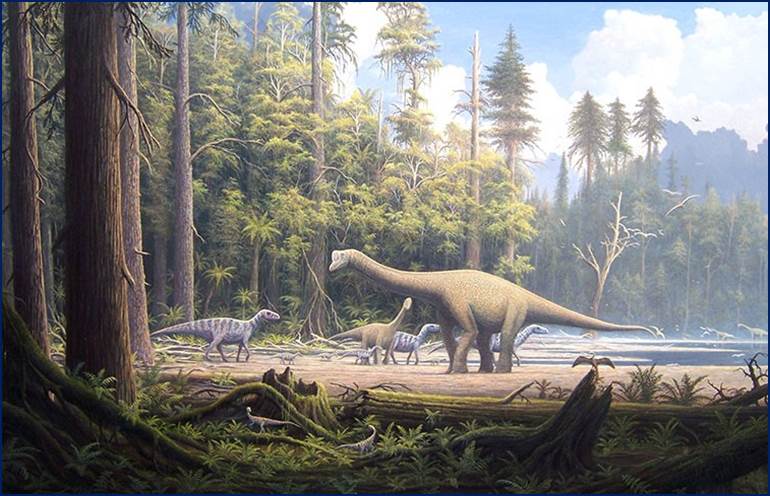

Dinosaur

tracks are direct evidence of how an animal was behaving at a specific moment

in time, millions of years ago © Greg Willis via Wikimedia Commons

'Australia's

Jurassic Park' the world's most diverse

Dino

Footprints in Spain...(remember original horizontality)

Why

Dinosaur Footprints Don't Erode – Explained

Following

is an article from the Natural History Museum in London, along with a couple

videos that may be helpful to your understanding.

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/dinosaur-footprints.html

Dinosaur

footprints: how do they form and what can they tell us?

By

Emily Osterloff

Fossilized

bones are some of the most tangible evidence of a dinosaur, but they aren't the

only way to study these prehistoric animals.

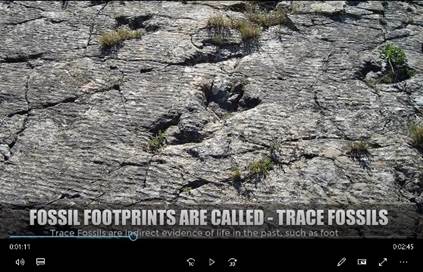

Preserved

footprints, also known as ichnites, are a type of trace fossil and a window

into the lives of dinosaurs.

They

formed in the same way our footprints do when walking on soft ground like mud.

But rather than being washed away, evidence of some of these reptiles'

movements has survived for millions of years.

How

do fossil footprints form?

The

impression or print left behind when an animal's hand or foot pushes into the

ground is called a track. Where they directly impact the ground is referred to

as a true track.

Ancient

shorelines and mudflats are common locations to find preserved dinosaur tracks

© Gerhard Boeggemann via Wikimedia Commons

As

an animal takes a step, the ground below the hand or foot is compressed. This

displacement forms features below the true track. These are known as

undertracks, underprints, ghost prints or transmitted tracks.

Undertracks

can extend anywhere from a few centimetres up to a metre below where the

animal's hand or foot pressed into the ground. In prints that are preserved -

for millions of years in the case of dinosaurs - sometimes you'll find both

tracks and associated underprints, and in other places only one or the other

will survive.

Tracks

can also survive as natural casts. These are made by the material that filled

the original track.

A

trackway is more than one consecutive footfall from the same animal.

A

single hand or footprint is called a track. More than one consecutive step by

the same animal is known as a trackway. This dinosaur trackway was found in the

Moenave Formation in Arizona, USA. © U.S. Geological Survey via Flickr

Why

do some footprints fossilize?

A

dinosaur could leave innumerable footprints, but only one skeleton. However,

for tracks to form and preserve, conditions must be just right.

The

consistency of the ground influences the shape, size and depth of the track and

any associated underprints. For a perfect print, the ground can't be too hard

or too soft.

If

the ground is too hard, the resulting print would be very shallow, show very

limited detail or not form at all.

If

the ground is too soft, the track could collapse in on itself. If these prints

survive, they would look distorted. For example, digit marks could turn into

slits instead of distinct fingers or toes. Once prints form, they could easily

degrade and be filled or washed away.

The

Red Gulch dinosaur tracksite in Wyoming, USA, features numerous fossil

footprints formed when the area was the coast of a prehistoric sea

The

soft ground of ancient shorelines or mudflats are common locations to find

fossilized dinosaur tracks. For example, those found at the Red Gulch

dinosaur tracksite in Wyoming, USA, were made during the Jurassic

Period when this area was the shoreline of the Sundance Sea.

Unlike

bones, which needed to be covered quickly once a dinosaur died to preserve as

much of the animal as possible, tracks first needed to be baked hard by the

Sun. This would have taken anywhere from days to months depending on the

conditions.

Only

then would a layer of mud, ash or similar help to preserve the tracks.

In

some places, fossilized tracks make it look as though dinosaurs would have been

walking up impossibly steep inclines, such as the near vertical Cal Orcko

tracksite in Bolivia. But this is where the geology of the ground has changed

dramatically over millions of years. The dinosaurs would have been walking over

much flatter ground - the Cal Orcko site was a riverbed around 200 million

years ago.

The

dinosaur tracks at the Cal Orcko site in Bolivia are found on an almost vertical

cliff face. Around 200 million years ago, this was a riverbed. Eight dinosaur

species have been identified on this site. © Hay Kranen via Wikimedia Commons

What

can dinosaur footprints tell us?

Dinosaur

tracks are a type of trace fossil.

These are evidence of an animal's activity when it was alive, but are not part

of the animal itself. Scientists that study this type of fossil are known as

ichnologists.

It

is almost impossible to tell exactly which species of dinosaur made a track -

for example, many theropods have similar-looking three-toed feet. Additionally,

bones and tracks don't line up exactly - the bones lack the soft tissue that

was part of the foot or hand that made the print

Bones

found close to a tracksite are unlikely to belong to the dinosaur that made the

tracks, as they would have fossilised under different conditions. Termination

trackways, where a dinosaur fossil is associated with its final steps, are

exceptionally rare.

Instead,

ichnologists are generally able to identify which dinosaur group made a track

using clues such as the size and shape of a print. Geographic location and the

age of the rocks may help narrow down the potential species.

A

sauropod trackway at the Copper Ridge dinosaur tracksite in Utah, USA © James

St. John via Flickr

Experts

can also determine whether a trackway was made by a bipedal or quadrupedal

dinosaur - one that moved on two or four legs. Bipedal footprints were made by

either theropods or ornithopods - although some of the latter, such as Mantellisaurus,

are thought to have spent time on all-fours too.

Theropods,

such as Tyrannosaurus, Baryonyx or Velociraptor,

had narrower and longer footprints than ornithopods. Theropod footprints

typically have long, slender toes and a V-shaped outline. Ornithopod tracks

lack distinctive claw marks and generally have a more rounded appearance with

wider digits.

Thyreophorans

(armoured dinosaurs) including stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, ceratopsians such

as Triceratops, and sauropods like Diplodocus, were

quadrupeds.

This

trackway was found in the Sonora Dinosaur Park in northern Mexico. These were

likely made by an ornithopod, which were plant-eating dinosaurs.

The

differences between ceratopsian, stegosaur and ankylosaur tracks are subtle.

Each had five fingers, but ceratopsians had four toes, stegosaurs had three and

ankylosaurs had three or four. Stegosaurs and ankylosaurs overlapped in time

and area, so telling their tracks apart can be tricky. Ceratopsians lived much

later than stegosaurs and the number of toes helps to distinguish them.

Ankylosaurs

generally had longer toes than ceratopsians. Additionally, ceratopsians may

have walked on the tips of their fingers so wouldn't leave a palm print,

whereas ankylosaurs walked with their palms flat on the floor.

Sauropods

produced the largest tracks of all dinosaurs. Their footprints were wide and

circular with five toes. Sauropods' handprints were smaller in comparison and

had a crescent-like outline. Most sauropods had claws on their hands, although

often only on the thumb, but evidence of these aren't always seen in tracks.

The feet usually had three claws.

In

some places only sauropod handprints are found. This may be

due to the type of the ground they were walking on and how they distributed

their weight. Some scientists have suggested this is evidence of sauropods

swimming, using their hands to pull themselves along rivers.

In

some places there are trackways made by multiple dinosaurs. These could have

been made at the same time or weeks apart. © James

St. John via Flickr

In

prints produced in perfect conditions, scientists may be able to spot skin

impressions or other evidence of the animals' soft anatomy, as well as claw

marks and indications of how flexible the digits were.

Tracks

are a record of how a dinosaur moved. Trackways show how long a dinosaur's

stride was. This can be interpreted from the spacing of the prints. It is

sometimes also possible to estimate how fast the dinosaur was moving.

A

series of parallel tracks may suggest that animals were moving in a group and

could indicate possible herd behaviour. Some experts propose that some

trackways with prints made by different types of dinosaurs are evidence of

prehistoric chase scenes. However, predator and prey prints in the same place

may have been made hours or even weeks apart.

A

direct link with the past

Dinosaur

tracks provide a snapshot of when these animals roamed across our planet. They

are direct evidence of how an individual was behaving at a specific moment in

time.

Fossilised

bones aren't necessarily found where the animal lived, they could have been

washed to a new location. But tracks were made by a dinosaur moving about its

environment - so they are an important link between these prehistoric animals

and the habitats they lived in.

Dinosaur

Footprints in Glen Rose, Texas! - Dinosaur Valley State Park