(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth Science Instructor: Arthur Reed, P.G.

Happy Fossil Friday!

Friday April 16, 2021

The

Days are Getting Longer: It’s Recorded in the Fossils

Earth

days have not always been 24 hours (currently getting longer), Earth

years (orbital period) have not always been 8,766 hours (it

fluctuates due to multiple variables but has remained close to its current

period), and our Moon’s orbital period has not always been what it is now (currently

getting longer). As far as the

length of one Earth day, it turns out that the fossil remains of small

Paleozoic animals called rugose corals have enabled geologists to approximate

the length of a typical Earth day 430 million years in the past (Paleozoic

Era).

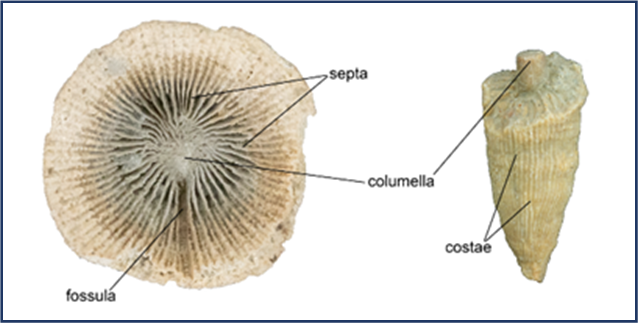

This Devonian rugose coral

highlights the small ridges that scientists count to determine how many days

were in a year when this coral was growing.

In

1963 Dr. John Wells from Cornell University published a paper on fossil coral

growth lines. He counted the smallest ridges on modern corals and discovered

that there were about 360 per year. He then counted these growth lines on

fossil corals and discovered that there were about 420 ridges on corals from

the Silurian (430 million years ago).

Other ages were counted also.

Based on the evidence that these individual ridges represented a single

day growth each, he did the calculations and determined one Earth day 430

million years ago was (365.25 days x 24hrs ÷

420 days) 20.9 hours. “At

what rate?” is this currently taking place you might ask. So, I’ll tell you: 0.0018 seconds per year longer. Okay, it’s a tiny amount, but it adds up over geologic time.

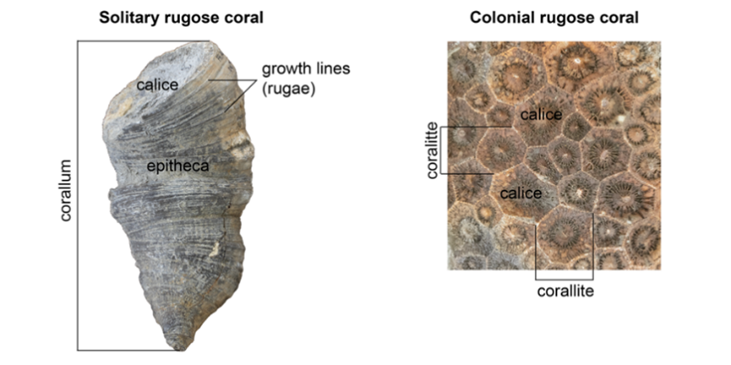

A

typical rugose coral fossil

A

reconstruction of Ordovician-aged solitary rugose corals on display in a

diorama at the American Museum of Natural

History in New York City.

A colony of the rugose coral ‘Acinophyllum stramineum’, from the Devonian Onondaga Limestone of Erie County, New York. Specimen is from the collections of the Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, New York (PRI 76812).

Rugose

coral (also called horn coral) fossil.

They can grow as individuals or in large colonies.

Click on 'expand' button in

lower right for best viewing of this 3D image.

BELOW IS One of many articles AVAILABLE on this subject

How

Ancient Coral Revealed the Changing Length of a Day

The lines on fossilized specimens show that millions of years ago,

it took 420 days for the Earth to complete an orbit around the sun.

KATE GOLEMBIEWSKI FEBRUARY 26,

2016

A

weathered fossil of a Devonian rugose coral colony

The earth spins, the sun rises and

sets, we have day and night. Each rotation cycle takes roughly 24 hours. But

that hasn’t always been the case—and eventually, it

will change again.

It takes the earth roughly 365 days

and six hours to orbit the sun. If we didn’t have Leap

Day on February 29 every four years to offset those extra hours, the calendar

would slowly creep out of sync with the seasons. But our practice of adding an

occasional extra day to our calendar won’t work

forever—as it turns out, the earth’s rotation is slowing down over time. Days

used to be much shorter. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the earth rotated

420 times around its axis in the time it took it to orbit the sun, rather than

365 and change. And fossilized corals from 430 million years ago can help prove

it.

Corals, like tree trunks, bear

records of growth periods—microscopically thin scars showing when the corals

were growing rapidly and when they weren’t. The lines

can help us differentiate between the busy growing seasons from year to year,

and even from day to day.

“When

a coral is growing, every day it puts down a fine layer of calcium carbonate,”

said Paul Mayer, the fossil invertebrates collections

manager at the Field Museum in Chicago. “Every day, there’s a deposit, and you

can see how they stack up into monthly deposits linked to the lunar cycle.”

“You can see seasonality, where the

corals grow more in the dry season than in the wet season,” he explained. “If

you count up all the little lines between seasonalities,

you get the number of days in the year.”

And those days per year are

different depending on when the corals lived. Corals from the Silurian Period,

444-419 million years ago, show 420 little lines between seasonality bands,

indicating that a year during that period was 420 days long. More recent corals

from the Devonian Period, a few million years later, show that the earth’s spin

had slowed down to 410 days per year.

So why is the Earth slowing down in

the first place? It has to do with the earth’s relationship to the moon. “The

moon used to be closer to us than it is now,” Mayer said. “In the Silurian

Period, the full moon would have looked a lot bigger on the horizon.” When the

Earth rotates, gravity pulls a bulge of ocean water toward the moon. That slow,

sloshing water slows down the planet’s spin by a tiny bit. And when the Earth

slows, its rotational energy is transferred to the moon, causing the moon to

move faster and pull away from the earth, centimeter by centimeter. And over

the course of millions of years, these infinitesimal adjustments to the earth’s

rotation and the moon’s distance add up, eventually changing the day and night

that our planet experiences.

“Who’d

have thunk that a fossil coral could tell you that

your calendars change over geologic time?” mused Mayer. “That’s one reason we

collect these things at the Field. They show us how our planet changes”—in

tiny, tiny differences that don’t matter until they do.

KATE GOLEMBIEWSKI is

a writer based in Chicago.