(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth Science Instructor: Arthur Reed, P.G.

Happy Fossil Friday!

Friday April 23, 2021

Trilobites

Used Their Legs to Breath?

All

animals (with rare exceptions) need oxygen.

Mammals use their lungs to get oxygen from the air, fish use their gills

to get oxygen dissolved in water.

Determining how ancient extinct animals gathered oxygen from their

environment has been one of the jobs of paleontologists. Researchers at University of California

Riverside recently used CT scanning to analyze recently found unusually

well-preserved trilobite fossils from the Paleozoic (542 million years ago to

251 million years ago). Based on the

delicate structures found on the legs, they have determined these creatures

were ‘leg breathers’! Fine filament

structures on their legs acted much the same as gills in modern marine

arthropods like crabs and lobsters. Read

the article below for more detail.

Anyone

applying to UC Riverside??

Trilobites

were Leg Breathers, New Research Shows

Apr

2, 2021 by News Staff / Source

Trilobites

had well-developed gill-like structures in their upper leg branches, according

to a new imaging study led by the University of California, Riverside.

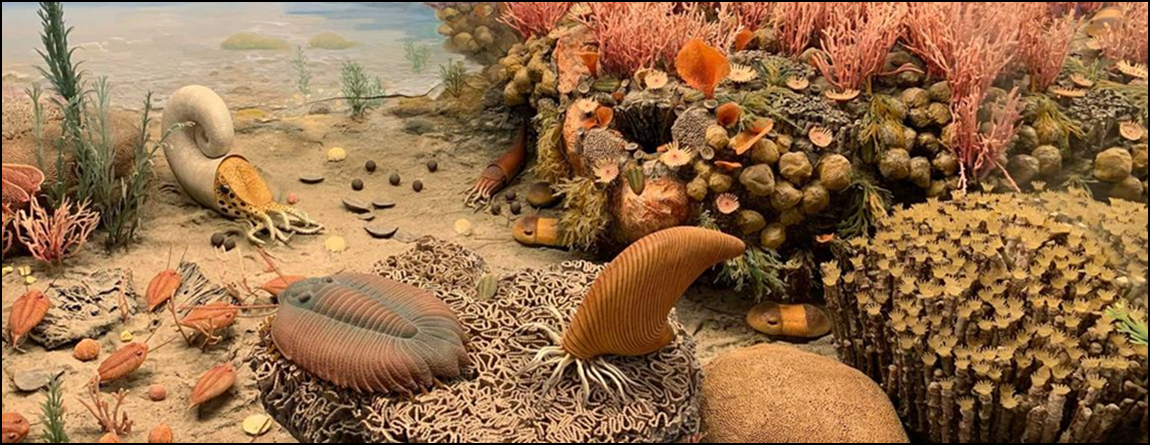

Trilobite fossil preserved in pyrite. Image credit: Jin-Bo Hou / University of California, Riverside.

Trilobites

are extinct marine arthropods that dominated the ecosystems of the Paleozoic

era.

They

appeared in ancient oceans in the Early Cambrian period, about 540 million

years ago, well before life emerged on land, and disappeared in the mass

extinction at the end of the Permian period, about 252 million years ago.

They

were extremely diverse, with about 20,000 species, and their fossil

exoskeletons can be found all around the world.

“Up

until now, scientists have compared the upper branch of the trilobite leg to

the non-respiratory upper branch in crustaceans, but our paper shows, for the

first time, that the upper branch functioned as a gill,” said lead author Dr. Jin-Bo Hou, a doctoral student in the Department of Earth

and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Riverside.

Dr.

Hou and colleagues examined the pyritized remains of two trilobite

species: Olenoides serratus from the

Burgess Shale and Triarthrus eatoni from the

Beecher’s Beds.

Triarthrus eatoni lived approximately 450 million years ago (Ordovician

period); Olenoides serratus lived

during the Cambrian period, about 500 million years ago.

“These

were preserved in pyrite — fool’s gold — but it’s more important than gold to

us, because it’s key to understanding these ancient structures,” said co-author

Professor Nigel Hughes, a paleontologist in the Department of Earth and

Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, and the

Geological Studies Unit at the Indian Statistical Institute.

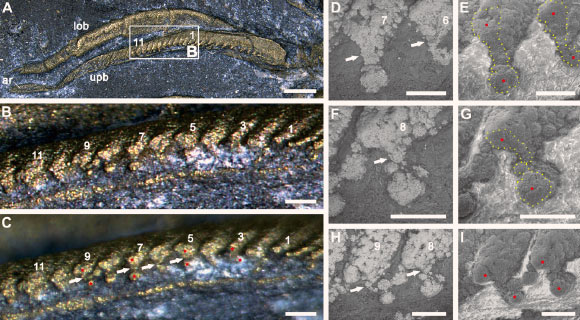

Dumbbell-shaped

filaments of Triarthrus eatoni: (A) dorsal view; (B) posterior view of the

truncated filaments in stacked (A); (C) same area of (B) with nonstack function; (D and E) the sixth and seventh

filaments showing dumbbell-shaped outline, tilted about 40° to the dorsal view;

(D) high-contrast backscattered electron (BSE) image; (E) high-contrast,

gaseous secondary electron (GSE) image; (F and G) the eighth filament showing

dumbbell-shaped outline, tilted about 40° to the dorsal view; (H and I) top view

of the eighth and ninth filaments showing dumbbell-shaped outlines; yellow

dotted lines mark the cross section of the filaments (E and G); arabic numbers are references for locating the cross

section of filaments in (A); asterisks locate the top and bottom inflated

marginal bulbs of dumbbell-shaped filaments; small white arrows indicate the

narrow central region of dumbbell-shaped filament. Abbreviations: ar – article of shaft, lob – lower branch of the limb, upb – upper branch of the limb. Scale bars – 500 μm in (A), 100 μm in (B

and C), and 50 μm in (D to I). Image credit:

Hou et al., doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe7377.

Using

a CT scanner, the researchers created 3D models of dumbbell-shaped filaments in

the upper limb branches of both Olenoides

serratus and Triarthrus eatoni.

“It

allowed us to see the fossil without having to do a lot of drilling and

grinding away at the rock covering the specimen,” said Dr. Melanie Hopkins, a

paleontologist in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of

Natural History.

“This

way we could get a view that would even be hard to see under a microscope —

really small trilobite anatomical structures on the order of 10 to 30 microns

wide.”

The

researchers could see how blood would have filtered through chambers in these

delicate structures, picking up oxygen along its way as it moved.

They

appear much the same as gills in modern marine arthropods like crabs and

lobsters.

“In

the past, there was some debate about the purpose of these structures because

the upper leg isn’t a great location for breathing apparatus,” Dr. Hopkins

said.

“You’d

think it would be easy for those filaments to get clogged with sediment where

they are. It’s an open question why they evolved the structure in that place on

their bodies.”

The findings appear

in the journal Science Advances.

_____

Jin-bo

Hou et al. 2021. The trilobite upper limb branch is a

well-developed gill. Science Advances 7 (14): eabe7377; doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe7377

Detailed view of trilobite leg. (Jin-Bo Hou/UCR)