(LINKS TO PAST FOSSIL FRIDAYS)

Community College (LRCCD)

Geology & Earth Science Instructor: Arthur

Reed, P.G.

Happy Fossil Friday!

Friday October 22, 2021

The Oldest Airborne Vertebrate Animal Was

a Reptile With Weird Wings

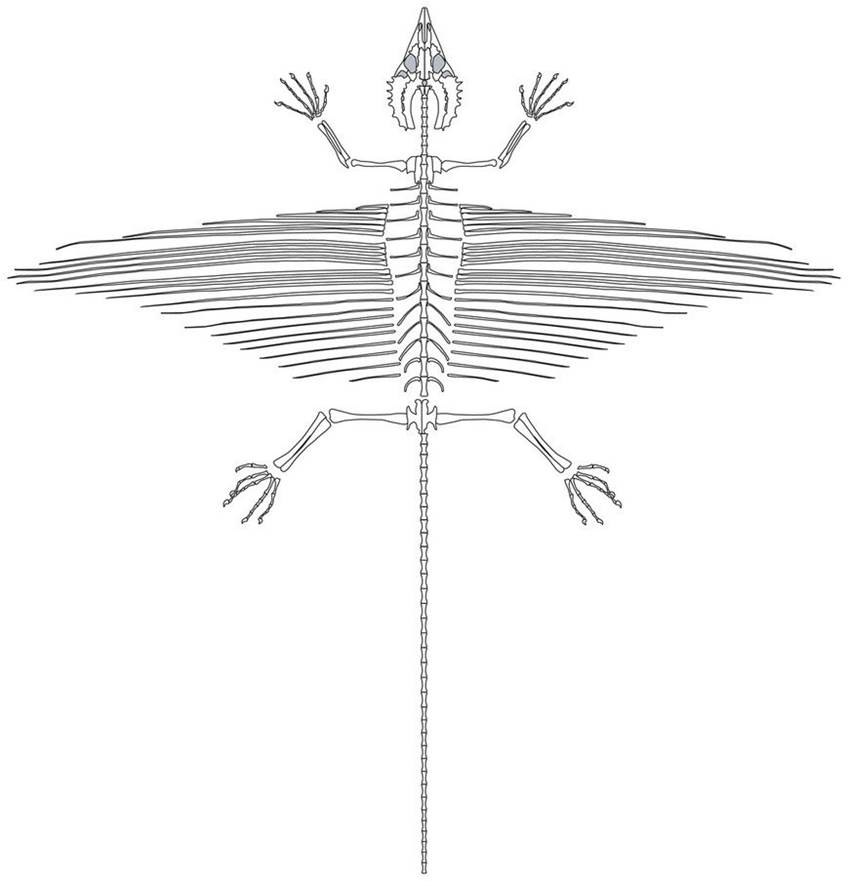

Artistic reconstruction of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli.

Proportions and anatomy after Pritchard et

al. (2021).

Before dinosaurs ruled Earth, there

were many small and fascinating reptiles.

One was the Weigeltisaurid in the late Permian around 255 million years

ago. Fossils of this animal have been

found in several locations around the world but only recently has one been

examined closely enough to understand that it was likely the earliest airborne

vertebrate. A fossil found in Germany in

1992 and stored in a German museum has now been analyzed by Smithsonian

paleontologists. They determined its

strange bone structure’s purpose was to support a thin membrane that gave it

the ability to glide through the air likely from one tree to another or to

simply parachute down. The Smithsonian article announcing the finding is

included below.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Oldest Airborne Vertebrate Animal Was a Reptile

With ‘Weird’ Wings

Paleontologists describe a

255-million-year-old weigeltisaurid fossil that likely glided through the air

with the help of expansive winglike membranes

October

13th, 2021

Scientists pulled this weigeltisaurid fossil out of an outcropping

of copper shale in Germany in 1992. Now, Smithsonian paleontologists have fully

described this animal, the oldest known vertebrate capable of gliding through

air. Pritchard et al. 2021

Since the Middle Ages,

humans have mined a rich deposit of shale stretching across Europe for copper,

zinc, silver and fossils. In 1992, a fossil collector

in eastern Germany pulled a strange skeleton out of the mining refuse from this

rocky layer. It had a pointy crown of horns, thin

limbs and peculiar rods stretching out from its chest.

These are a really weird set of bones. They do not seem to exist in

pretty much any other vertebrate animal, said Adam Pritchard, an assistant

curator of paleontology at the Virginia Museum of Natural History and former

Peter Buck postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian National

Museum of Natural History.

The fossil, it turns out,

is an ancient reptile named Weigeltisaurus jaekeli, a reptile that

lived over 250 million years ago before the dinosaurs. Pritchard and Hans-Dieter Sues, curator of vertebrate

paleontology at the museum, have published a new detailed analysis of the specimen in

the scientific journal PeerJ. They posit that the

animal, known as a weigeltisaurid, used those bony rods to support winglike

membranes used for gliding, making it the oldest-known airborne vertebrate

animal.

Weigeltisaurus jaekeli likely used its wide, winglike

membranes to glide from branch to branch in the late-Permian

forest. Paleontologists reconstructed the reptile’s anatomy in this

drawing to illustrate its skeleton’s proportions. Pritchard et al. 2021

A strange specimen

The fossil hunter found

the strange skeleton by splitting pieces of shale, cracking the fossil

into two slabs. One slab ended up in the hands of a private collector and

likely contains pieces of the reptile's bones. The other slab held most of the

skeleton and landed in the collection of the State Museum of Natural

History in Karlsruhe, Germany. Scientists pinpointed the fossil in the second

slab as a Weigeltisaurus, which was first described from another

fossil in 1930, but the reptile's body shape still remained

an enigma to paleontologists.

Over the years, some

researchers suggested that the long bones protruding from the specimen’s

abdomen could have allowed the animal to glide through the air like a flying

squirrel. But the skeleton in the fossil is curved in on itself and some bones

are overlapping, making it hard to tell if they’re just ribs, or something

else.

Researchers cleaned the Karlsruhe fossil to expose its bones more

clearly before analysis. The positioning makes it difficult to deduce the

function of the long horizontal bones pictured at the fossil’s center. Diane Scott

“There are very few

things like it,” Sues said of the fossil. A few other specimens from the same

species have also been unearthed in England, Russia

and Madagascar, but the fossil housed in the Karlsruhe Museum provides the most

complete example of the animal’s anatomy. “This is definitely the one that

brings it all together,” Pritchard said.

Pritchard saw the

skeleton referenced in the scientific literature over the years as a grad

student researching the evolution of early reptiles during the Permian Period,

which lasted between 299 and 251 million years ago. “But no one had really gone

in and done a very fine, detailed analysis of the skeleton of these animals.” When Pritchard

came to the Smithsonian as a postdoc in search of a meaty project to dig his

teeth into, Sues suggested he take a closer look at

the weigeltisaurid.

Quality fossil time

Pritchard flew to

Germany for a week to pore over the fossil at its home in the Karlsruhe museum’s

collections. ”I'm of the mind that if you're going to

make a fossil the focus of a study you should spend a very large amount of

quality time with it in person, ” he said.

He took pages of copious

notes, making an inventory of all the individual bones and building his own

interpretation of how they all might fit together. ”And

then I photographed the heck out of it, ”Pritchard said, to be sure he wouldn’t

miss one tiny detail in the bones once he came back to the Smithsonian.

The weigeltisaurid specimen used in the bulk of Pritchard and

Sues’ study is housed in the State Museum of Natural History in Karlsruhe,

Germany. Adam Pritchard

After painstakingly

measuring every rib, finger and toe, Pritchard laid out the weigeltisaurid”

bones in several

drawings and diagrams. He also mapped where the animal might fit on the reptile

family tree by comparing each of its anatomical traits with those of other

ancient lizards. Though it probably looked something like a chameleon, the

weigeltisaurid belongs to an evolutionary line that split off from the lizards,

crocodiles and snakes we know today.

”These are a more ancient lineage than any of those

animals,” Pritchard explained.

Unique gliders

Initially, Pritchard

looked at this project as a chance to explore a curious fossil on a deep level.

”But as I got into the work, it became clear to me

that there was one question that kind of remained. And that is the identity of

the bones that seem to have formed the gliding membrane,” he said.

Pritchard and his

colleagues’ analysis shows that there are more wing

bones than vertebrae and that they lay separate from the rest of the skeleton,

confirming that they would have supported two wide flaps extending from each

side of the animal’s abdomen. This is a singular trait, Sues

explained. There are gliding lizards that exist today, but their ‘wings’ are

attached to their ribs, he said.

While Pritchard and Sues

are confident that weigeltisaurids were gliders, there’s not a lot else known about

the animal’s life history. ”I would love to know how

they grew,” Pritchard said. ”What did it look like

when it popped out of the egg?” He also wonders about what the weigeltisaurid

snacked on. His best guess is bugs, but he can’t be totally sure unless some

direct fossil evidence turns up. ”We don’t have a

weigeltisaurid with insect material inside its abdominal region. But that would

be cool,” Pritchard said.

Though he’s not

currently working on these questions, Pritchard said that learning more about

weigeltisauird and its relatives can give us a better appreciation for the

diversity of reptiles - even before dinosaurs came on the scene. ”Among paleontologists there’s this sense that once you get

into the age of dinosaurs, that’s when reptiles really take off, develop all

kinds of amazing features and just come into their own,” he said. But earlier

animals like Weigeltisaurus are proof that reptiles have

always been ”super weird,” he explained. ”They’re doing strange things that, if we didn’t have the

fossils, we never would have expected. ”

Tess

Joosse | | READ MORE

Tess Joosse is an intern in the Smithsonian National Museum of

Natural History’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Her writing

has appeared in Science, Scientific American, Inside Science, Eos, Mongabay and

the Mercury News, among other outlets. Tess recently graduated from the

University of California, Santa Cruz with an MS in science communication. She

also holds a BA in biology from Oberlin College. You can find her at https://www.tessjoosse.com/.

(and: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY)